|

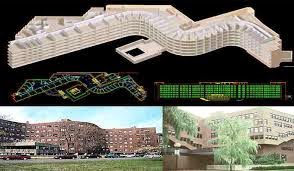

| ORGANIZING THE PLAN |

This whole process of establishing in detail the building’s three-dimensional organisation is best

explored through the medium of drawing; a facility for drawing in turn facilitates designing in that ideas can be constantly (and quickly) explored and evaluated for inclusion in the design, or rejected.

Circulation

envelope.

Essentially, such devices will serve to punctuate these routes by variations in lighting, for example, which may well correspond to ‘nodes’ along the route like lobbies for vertical circulation. Further punctuations of the route can be achieved by ‘sub-spaces’ off the major route which mark the access points to cellular accommodation within the building.

Such ‘sub-spaces’ may also provide a useful transition between the route or concourse, and major spaces within the building.

Vertical circulation

The location of vertical circulation also contributes substantially to this idea of ‘reading’ a

building and clearly is crucial in evolving a functional plan. There is also a hierarchy of

vertical circulation; service or escape stairs, for example, may be discreetly located within

the plan so as not to challenge the primacy of a principal staircase.

Moreover, a stair or ramp may have other functions besides that of mere vertical circulation;

it may indicate the principal floor level or piano nobile where major functions are

accommodated, or may be a vehicle for dramatic formal expression.

The promenade

Closely associated with any strategy for circulation within a building is the notion of ‘promenade’ or ‘route’. This implies an understanding of buildings via a carefully orchestrated series of sequential events or experiences which are linked by a predetermined route. How the user approaches, enters and then engages with a building’s three-dimensional organization upon this ‘architectural promenade’ has been a central pursuit of architects throughout history.

The external stair, podium, portico and vestibule were all devices which not only isolated a

private interior world from the public realm outside but also offered a satisfactory spatial

transition from outside to inside.

The exemplar

By the late 1920s Le Corbusier had developed the notion of promenade architecturale to a

very high level of sophistication. At the Villa Stein, Garches, 1927, a carefully orchestrated

route not only allows us to experience a complex series of spaces but also by aggregation

gives us a series of clues about the building’s organization. The house is approached from

the north and presents an austere elevation with strip windows like an abstract ‘purist’

painting. But the elevation is relieved by devices which initiate our engagement with

the building. The massively-scaled projecting canopy ‘marks’ the major entrance and relegates the service entrance to a secondary role.

Spatial hierarchies

Whilst such patterns of circulation and the ordering of ‘routes’ through a building allowus to ‘read’ and to build up a three-dimensional picture, there remains the equally important question of how we communicate the essential differences between the spaces which these systems connect. This suggests a hierarchical system where spaces, for example, of deep symbolic significance, are clearly identified from run-of-the-mill elements which merely service the architectural programmed so that an organisational hierarchy is articulated via the building. Similarly, for example, when designing for the community it is essential that those spaces within the public domain are clearly distinguished from those deemed to be intensely private.

This whole question of spatial hierarchy may also be applied to sub-spaces which are subservient to a major spatial event like side chapels relating to the major worship space

within a church. At the monastery of La Tourette, Eveux-sur-Arbresle, France, 1959, Le Corbusier contrasted the stark dimly-lit cuboid form of the church with brightly-lit side chapels of sinuous plastic form which were further highlighted by the application of primary colour against the grey be´ton Brut of the church (Figure 3.54). Such a juxtaposition served to heighten not only the architectural drama but also the primacy of the principal worship space.

Inside-outside

Establishing and then articulating these spatial hierarchies within the context of a functional

plan has exercised architects throughout history; a system of axes employed by Beaux Arts architects, for example, greatly facilitated this pursuit. But many architects of modernist persuasion, in their desire to break with tradition, have shed such ordering devices and have espoused the liberating potential that developments in abstract art and building technology seemed to offer.

Establishing and then articulating these spatial hierarchies within the context of a functional

plan has exercised architects throughout history; a system of axes employed by Beaux Arts architects, for example, greatly facilitated this pursuit. But many architects of modernist persuasion, in their desire to break with tradition, have shed such ordering devices and have espoused the liberating potential that developments in abstract art and building technology seemed to offer.

Comments

Post a Comment